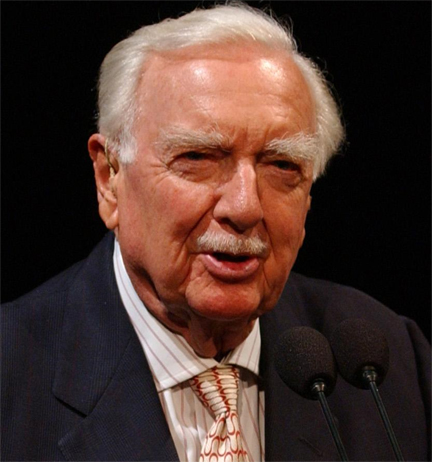

Leigh with her friend Tara at the March

My sister-in-law Leigh took off early yesterday morning for the Women’s March on Washington. I stayed home.

One reason for my not marching was the state of my knees. I get tired after a few hours of standing at my holiday retail job. I have a feeling walking around Washington for a day would do me in for a week or more.

I also have a fear of crowds!

More importantly, however, group protest is not my mode of self expression, particularly in this case. I got my first invitation to the march the morning after Donald Trump’s election. It seemed—and seems—to me too soon to be protesting. I would have preferred to wait and protest some specific presidential action or policy rather than the president himself.

Nevertheless, I support the right to free speech of my friends and relatives who chose to march. In fact, I happily lent my BEAUTIFUL new pink hat to Leigh to wear on her march. (See photo above.)

We all speak and protest in our own ways. I deal with things that upset me—and I have to admit that I’m not a fan of our new president—by writing and singing and talking. And staying positive.

Here’s what I want to do in the months ahead: I want to emulate the folks from Broadway’s Concert for America. They will inspire me to do creative things and to support organizations and people who can keep our country strong and wonderful and charitable and generous and (yes!) great.

I want to write passionately about things that matter. In my case, this is usually food and books—but food and books sustain life and give it meaning.

I want to sing whenever I can. In my opinion, there is very little in this world that a show tune or a spiritual can’t make just a little bit better. Music connects us as human beings. It helps us mourn, comfort each other, and then move forward and celebrate.

Above all, I want to be a good neighbor on my road, in my community, and in my world. I want to stay in contact and sympathy with all the people I know, whether they voted for Trump or Clinton or Mickey Mouse. And I want to continue to meet and converse with new people. The one thing I think Donald Trump got right in his inaugural address is the idea that our nation is about all of its citizens.

So I’ll be marching with my fingers and my voice and my smile. Not all at once but one step at a time. I hope to encounter lots of you along the way.